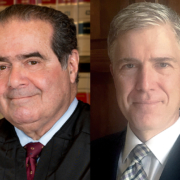

When President Donald Trump said he would nominate a Supreme Court justice in the mold of Justice Antonin Scalia, who died one year ago on Feb. 13, everyone knew that meant someone who shares Scalia’s originalist philosophy of constitutional law.

But who expected that the appointee, Neil Gorsuch, would be another Georgetown graduate? And one who apparently once shared the late Catholic jurist’s disapproval of “liberal” trends in Catholic education?

To be precise, Scalia graduated from the Jesuits’ Georgetown University in 1957, and Gorsuch graduated from Georgetown Preparatory School in 1985. But years earlier, both institutions sprang from the same Georgetown College that Father John Carroll (the future archbishop of Baltimore) founded in 1789. In fact, there was little distinction between the secondary school and the college for nearly a century. The Preparatory School finally separated and moved from Washington, D.C., to its present location in Bethesda, Maryland, in 1919.

‘Not Catholic Anymore’

When Father Carroll founded Georgetown, it was with great hope that the school would help firmly establish the Catholic Faith in America.

“The object nearest my heart now, and the only one that can give consistency to our religious views in this country, is the establishment of a school, and afterwards a Seminary for young clergymen,” he wrote in 1785 to Father Charles Plowden in England.

A historian at Georgetown Prep, Steve Ochs, has written that the College once embraced the traditional view of Catholic education—that its aim is to form young people in Christ and for Christ: “Most importantly, the Jesuits of Georgetown regarded the Christian formation of students as their primary mission. Knowledge and skills, although important, were approached as a means to an end: the knowledge and love of God.”

The University today, sadly, no longer has this view of education. This is most apparent in the dossier on Georgetown scandals that accompanied the late William Peter Blatty’s petition to the Vatican.

In 2014, Justice Scalia famously declared that “Georgetown University is not Catholic anymore.” In his days at Georgetown, Scalia said, “they rolled you out of bed to attend Mass. Not anymore.”

According to The Remnant:

One little vignette still fondly remembered by the Justice harks back to what Georgetown was.

At his final oral exam prior to receiving his degree (History), Scalia was breezing along when Dr. Wilkinson, the chairman of the department who presided over the three professor panel, asked this question: What was the most important event in the history of the world?

The confident candidate thought, “I have done very well up to here and there is no wrong answer to this one,” but as he responded Prof. Wilkinson continued to shake his head signaling that the student had it all wrong. Was it the Battle of Waterloo, or the Greek valor at Thermopylae? The panel member remained unimpressed with the candidate’s answers.

Finally, Dr. Wilkinson replied: “Mr. Scalia it was the Incarnation, when Christ became a man that is the correct answer.” One seriously doubts that Dr. Wilkinson’s question is ever asked at Georgetown examinations today, and if it were, clearly his response would no longer be considered correct. Despite his answer, Antonin Scalia graduated from Georgetown U. summa cum laude, no mean feat in those days in which grades were not “curved,” and no one had ever heard of “grade inflation.”

The prior year, Scalia addressed Catholic students at the University of Virginia and also criticized Georgetown University:

“When I was at Georgetown, it was a very Catholic place. It’s not anymore—and that’s too bad,” Scalia said. “What has happened to Catholic universities, that they would lose their reason for being?”

He said the Catholic Church as a whole “has been in trouble for a while,” having lost some of its zeal for evangelization, for which Catholic education is the Church’s primary tool.

Need for Moral Formation

Justice Scalia didn’t come to that view toward the end of his life; he had deep concern for Georgetown and Catholic education generally for many years. In 1997, Scalia addressed The Cardinal Newman Society’s national conference in Washington, D.C., and he urged Catholic colleges to hold on to their Catholic beliefs:

The American landscape is strewn with colleges and universities, many of them the finest academically in the land, that were once denominational, but in principle or practice no longer are. With foolish sectarian pride I thought that could never happen to Catholic institutions. Of course I was wrong. We started later, but we are on the same road.

Scalia believed strongly in the continued need for Catholic education in today’s society, “because of the moral environment in which its work is conducted—an environment that sternly disapproves what the Church teaches, and in most cases what traditional Christianity has always taught, to be sinful.”

For that reason, the Catholic college must not shy away from “moral formation,” he said. “Catholic universities cannot avoid that task, and indeed betray the expectations of tuition-paying Catholic parents if they shirk it,” he argued.

Again in 2011, in a speech given at Duquesne University School of Law, Scalia adviocated moral formation:

Our educational establishment these days, while so tolerant of and even insistent on diversity in all other aspects of life, seems bent on eliminating the diversity of moral judgment, particularly moral judgment based on religious views. I hope this place will not yield, as some Catholic institutions have, to this politically correct insistence upon suppressing moral judgment, to this distorted view of what diversity in America means.

Scalia told the audience that moral formation “has nothing to do with making students better lawyers, but everything to do with making them better men and women. … Moral formation is a respectable goal for any educational institution, even a law school.”

He added, “A Catholic law school should be a place where it is clear, though perhaps unspoken, that the here-and-now is less important, when all is said and done, than the hereafter.”

An Episcopalian Conservative

Scalia’s high school experience, like his experience of 1950s Georgetown, was very good. He said that he became a “serious Catholic” at the Jesuit Xavier High School in New York, because of the “thoroughly religious atmosphere of the school.”

Gorsuch also attended a Jesuit high school, and like Scalia, he was a successful student. Scalia graduated in 1953 as valedictorian and first in his class at Xavier. Three decades later, Gorsuch was a top debater and was elected student body president at Georgetown Prep.

Both were fiercely conservative even as young men. “This kid was a conservative when he was 17 years old,” said Scalia’s classmate and future New York State official William Stern. “An archconservative Catholic. He could have been a member of the Curia. He was the top student in the class. He was brilliant, way above everybody else.”

Gorsuch, too, was openly conservative, but he found himself in a different environment than the “thoroughly religious” Xavier that Scalia attended. According to the Jesuit America magazine, Gorsuch sparred with both political and theological liberals at Georgetown Prep, even though he was an Episcopalian:

As a student at the tony, Jesuit-run Georgetown Preparatory School, Neil Gorsuch, the son of a Reagan administration official, was known as something of a conservative firebrand among the mostly center-left student body and faculty.

In the 1980s, students at the D.C.-area boarding school spent the minutes before student government meetings hashing out the political debates of the day.

Mr. Gorsuch, who was nominated on Jan. 31 to the Supreme Court by President Donald J. Trump, participated in the informal debates, where he was routinely teased, accused of being “a conservative fascist.” No shrinking violet, he would shoot back, taking on the liberal ethos of the school and even arguing with religion teachers about the liberal theological trends in vogue at the time.

Nevertheless, America reports, Gorsuch was popular and appears to have had a sense of humor, which was the cause of a recent flurry of news reports claiming that President Trump’s Supreme Court nominee had founded and led a “Fascism Forever” club in high school.

Ochs, the historian who teaches at Georgetown Prep and remembers Gorsuch from years ago, explained to America that the club was “a total joke.” Among the activities that Gorsuch listed in his high school yearbook, he identified himself as “Founder and President” of the “Fascism Forever Club.” (He also claimed to be a “Lousy Spanish Student” and president of the “Committee to reform The Beast.”)

“There was no club at a Jesuit school about young fascists,” Ochs told America. “The students would create fictitious clubs; they would have fictitious activities. They were all inside jokes on their senior pages.”

But it was not all fun at the liberal Jesuit school, apparently.

“There were some teachers who were ultra-liberal, and he would spar with them in class, like in religion class specifically, I remember, but always in good nature,” Ochs told America.

Distinguished Alumni

There’s been no sparring with Georgetown Prep this year over its graduate’s nomination to the Supreme Court.

“We are proud to have a son of Georgetown Preparatory School, a Catholic, Jesuit school founded the same year the United States Supreme Court was established, nominated to the nation’s highest court,” said Father Scott R. Pilarz, S.J., the school’s president, in a public statement. “All of us at Prep send our prayers and best wishes.”

America also reports that 70 of Gorsuch’s 90 classmates wrote a letter to Senators urging his confirmation.

If their wish is granted, Gorsuch is widely expected to be a strong advocate on the Court for religious freedom and the protection of human life from abortion and physician-assisted suicide.

When accepting his nomination, Crux reports that Gorsuch thanked his “friends, family and faith” for keeping his feet on the ground.

This article first appeared at The National Catholic Register.