Catholic Curriculum Standards: Faithful to the Core

When Jill Annable began her role as assistant superintendent in the Diocese of Grand Rapids, the staff was working on rewriting its curriculum standards for all subject areas and all grades, to try to integrate Catholic identity across all content areas.

Educators who have worked on school standards know that it’s no small task. Fortunately for Annable and the Diocese of Grand Rapids, timely help provided just what they needed.

“We were drafting and drafting,” Annable recalled in a recent podcast produced by the National Catholic Educational Association (NCEA), where she now serves as the executive director of academic excellence. She remembers when her superintendent walked into her office and excitedly shared, “It was published, you can use it!” She meant the Catholic Curriculum Standards, which had just been released by The Cardinal Newman Society.

“When I opened it up, I realized that it was the missing piece,” Annable told Dr. Denise Donohue, the Newman Society’s deputy director of K-12 programs, who was also a guest on the podcast. “It was the language I needed to use without trying to invent it ourselves.”

The Diocese of Grand Rapids isn’t the only diocese to find our Catholic Curriculum Standards helpful.

“Since, in every school, the curriculum carries the mission, these Catholic Curriculum Standards are an invaluable contribution to Catholic schools everywhere,” says Father John Belmonte, S.J., superintendent of the Diocese of Venice.

“Catholic schools have benefited from the standards-based reform movement in education with one notable exception: the absence of rigorous standards rooted and grounded in our Catholic tradition,” Fr. Belmonte continues. “Implementation of the Catholic Curriculum Standards will provide a renewed sense of mission for our Catholic schools operating within the increasingly secularized world of education today.”

Today, at least 28 diocesan school systems and many other Catholic schools across the United States—serving more than 270,000 students—use the Catholic Curriculum Standards to replace or supplement their existing diocesan standards.

Common Core concerns

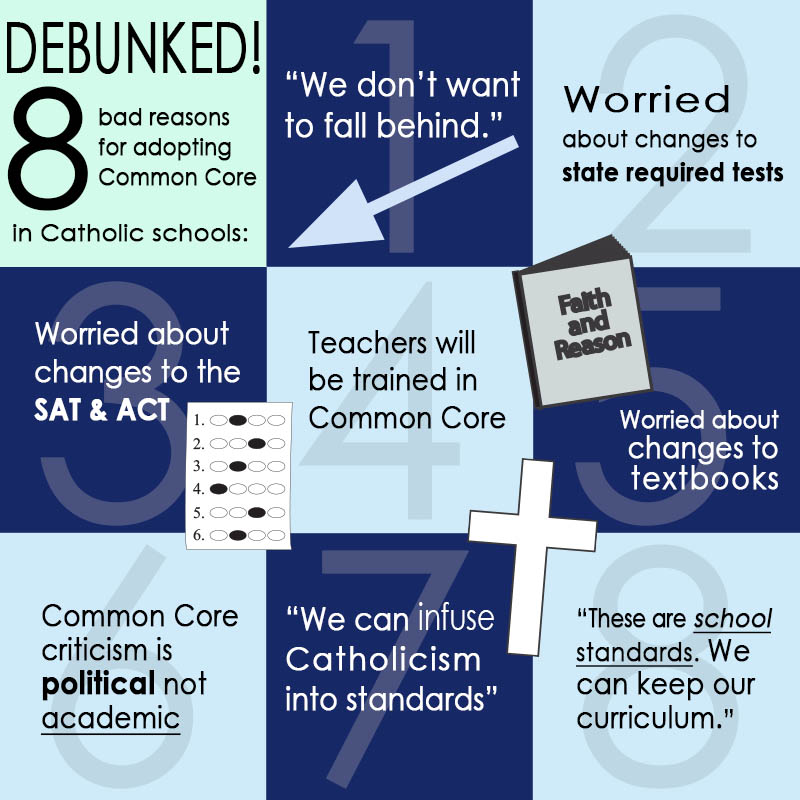

Over the last decade, many public and Catholic schools across the country have adopted the Common Core State Standards. But the Common Core is a secular program designed with utilitarian goals—to lift up under-achieving public school students for success in college and careers. Aside from disagreements about its embrace of controversial methods and educational theories, the Common Core was never intended for the fullness of human flourishing that the Church demands of Catholic education.

Giving voice to the concerns of many Catholic families, the Newman Society’s “Catholic Is Our Core” program has informed Catholic educators about shortcomings of the Common Core. It began with a campaign by mail, email, social media and web outreach to educate Catholic families, leaders and educators and to urge Catholic schools to reject or at least radically adapt the Common Core standards to the mission of Catholic education. Our analyses have been featured in national Catholic publications and on Catholic radio and television.

In 2013, consistent with many of the Newman Society’s concerns, a cadre of Catholic college professors (132 altogether) signed a joint letter stating they were “convinced that Common Core is so deeply flawed that it should not be adopted by Catholic schools” and that those who had adopted it “should seek an orderly withdrawal.” The following year, the education office of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops issued a statement warning that the Common Core standards alone are insufficient for Catholic schools.

Today it is clear that the Common Core has failed to produce the promised improvements in both public and Catholic schools, and states and dioceses are pulling back from the misguided standards. What now should replace them? The Common Core experience, though messy, helped spark widespread interest among Catholic bishops, educators and families for something better. It is toward that goal that the Newman Society’s staff turned, striving for a uniquely Catholic set of standards.

Providing a solution

In 2015, the Newman Society resolved to answer a question posed by several bishops and diocesan superintendents: “If Catholic education is distinct from secular education, then where are the standards for Catholic educators?”

Our response is the Catholic Curriculum Standards, rooted firmly in the Church’s teaching on Catholic education and her long tradition of liberal arts formation in truth, goodness and beauty.

“The first time I read them, I thought this isn’t the ‘Catholic Common Core.’ This is the why and the how, and gives the beauty to why we teach math, why we inquire in science. You wouldn’t just slap these standards on top of Common Core,” said Annable.

The standards specifically cover the core subjects of English, history, scientific topics and mathematics, but Annable says her diocese was able to apply the standards to elective courses as well, which she says was a “true gift.”

Developing the Catholic Curriculum Standards was a labor of love. The Newman Society staff spent two years analyzing Church documents to identify key elements the Church expects to find in all Catholic schools. Those were distilled into the Newman Society’s Principles of Catholic Identity in Education, which are similar to Archbishop Michael Miller’s “essential marks of Catholic schools,” but capturing more of the language and balance of Vatican documents.

For the standards project, the Newman Society’s Dr. Dan Guernsey and Dr. Denise Donohue studied these Principles, Church documents, scholarly works related to Catholic education and the Catholic intellectual tradition, and books articulating the nature of liberal arts and classical education. They also met with more than a dozen professors from faithful Catholic colleges to consider what knowledge and formation one should expect from a Catholic school graduate.

A Catholic foundation

The Catholic Curriculum Standards include “dispositional” standards for each academic discipline, along with expected “content” or “intellectual” standards.

As Guernsey and Donohue were reviewing Church documents for curricular application, they noticed much discussion about the formation of dispositions within students. That topic was much more prominent than concerns about course content. For example:

The Catholic school aims at forming in the Christian those particular virtues which will enable him to live a new life in Christ and help him to play faithfully his part in building up the Kingdom of God. (The Catholic School, 1977, 36)

Creating the dispositional standards has proven beneficial for Catholic schools needing to address the National Standards and Benchmarks for Effective Catholic Elementary and Secondary Schools (NSBECS) for accreditation purposes. Schools using the Catholic Curriculum Standards, along with a solid virtue program, are able to address numerous benchmarks required for accreditation.

For the mathematics standards, the Catholic perspective is primarily dispositional. The Catholic Curriculum Standards expect students to identify truth and falsehood in relationships and to acquire the mental habits of “precise, determined, careful and accurate questioning, inquiry and reasoning.”

Examples of English literature standards include, “Explain how Christian and Western symbols and symbolism communicate the battle between good and evil and make reality visible” and “Demonstrate how literature is used to develop a religious, moral and social sense.” The English standards especially earned high praise from Sandra Stotsky, Ed.D., who is a national consultant in standards development and author of the highly regarded Massachusetts Academic Standards. She proved very helpful to the Newman Society’s work as well.

“The K-12 standards and suggested readings in Appendix C for the reading/literature curriculum in Catholic schools reflect more than the uniqueness of their intellectual tradition,” Stotsky said. “They also provide the academic rigor missing in most public-school English language arts curricula.”

Inspiring and crucial

The impact of the Catholic Curriculum Standards over the past five years has been exciting.

“The Catholic Curriculum Standards are EXACTLY what I have been wanting—specific in the areas of faith formation and the pursuit of goodness, truth and beauty, but broad enough to give the teachers latitude in their instructional methods,” said Lynette Schmitz, the principal of St. John Paul II Preparatory School, a Catholic classical hybrid school in St. Louis, Mo.

Derek Tremblay, headmaster of Mount Royal Academy in Sunapee, N.H, agrees. “I thoroughly love the Standards that The Cardinal Newman Society has put out and have yet to find anything comparable.”

Another Catholic school principal, Janice Martinez, principal of Holy Child Catholic School in Tijeras, N.M., said: “I find the standards of education you have recently publicized to be inspiring. I believe the work you do is crucial and support your mission.”

Despite the great success of the Catholic Curriculum Standards, there’s much more work to be done. Standards help establish a school’s priorities and promote the right outcomes of truly faithful Catholic education. But curriculum standards alone can never determine what happens in the classroom.

We hope that the Catholic Curriculum Standards will promote greater integration of the faith in every academic discipline, leading eventually to new and improved textbooks, lesson plans, teacher training and school evaluation.

The complete Catholic Curriculum Standards are available to educators at no cost on the Newman Society’s website, together with helpful appendices and resources to support implementing the standards. Feel free to reach out to The Cardinal Newman Society if you are interested in knowing more about the standards and how they might be used in your diocese, school or homeschool program.

St. Agnes School, St. Paul, MN

St. Agnes School, St. Paul, MN